|

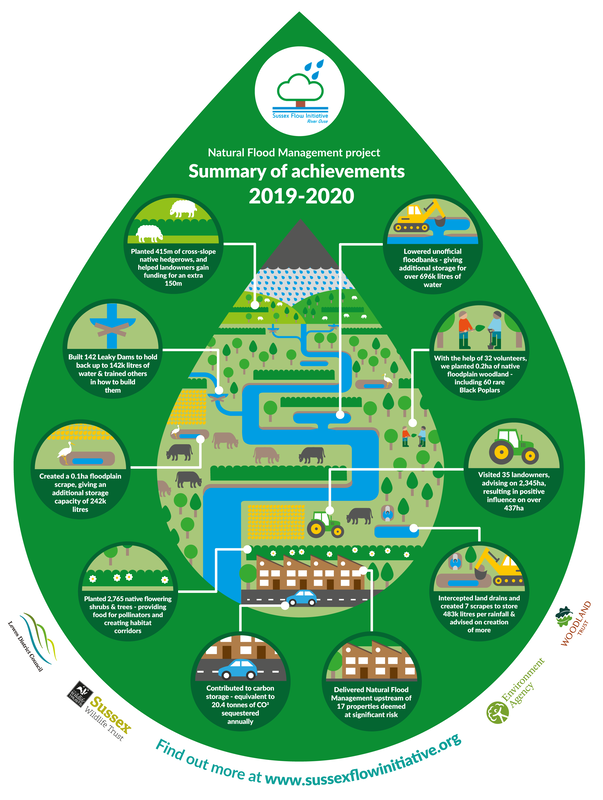

The Sussex Flow Imitative (SFI) provides working examples of Natural Flood Management (NFM) techniques and best practice NFM projects. We promote a landscape scale approach to reducing flood risk and water shortages, and to promoting the wider uptake of NFM in other suitable catchments. Over the past five years SFI has delivered a large number of NFM projects, demonstrating a range of different NFM techniques. These provide case studies and working examples of how NFM can be practically applied in lowland catchments. The main NFM methods SFI have used over the last five years are: Restoring natural processes through reconnecting river channels, meanders and floodplain washlands - area equivalent to 4.95 hectares of floodplains have been reconnected. Providing advice on land use and controlling excessive run-off and erosion - advice given to 11% of catchment area. Increasing the roughness of the catchment through enabling the expansion of woody areas and planting 10.2km of native hedgerows, primarily across slopes and on floodplains.

Increasing space for water within the catchment, through creating ponds and scrapes that store surface water - area equivalent to 1.92 hectares of freshwater habitat created. litres of flood water stored in series of ponds and scrapes across the catchment.

This is just a snapshot of the incredible achieves of the SFI project over the last five years, please read the full report to find about all the other amazing things we have done - full report.

0 Comments

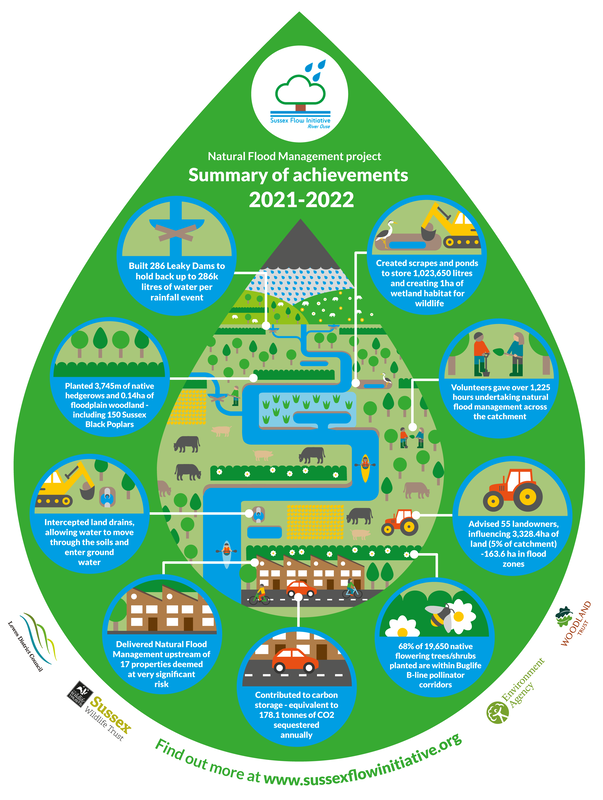

This year we celebrated ten years of incredible work in creating a climate resilient landscape for both people and wildlife. Easing of restrictions from the C19 pandemic meant we were able we were able to deliver a significant amount of Natural Flood Management across the Ouse Catchment this year. A few highlights from 2021/22:

The above is just a selection of the work undertaken in 2021/22, the full annual report and the summary report go into great detail on what has been achieved and its impact. Thank you to all our landowners, volunteers and partner organisation for their support in a challenging year for all. There are a number of ways that woodland and hedgerows can help slow and store water, and reduce flood peaks. On floodplains and when planted across slopes, trees act as a physical barrier to overland flow delaying the movement of water downhill and downstream. Trees also help to improve soil health and to reduce compaction, increasing how effective water soaks into the ground. They also deliver multiple other benefits, including increases in biodiversity through providing important habitat and food for a range of different animals, carbon sequestration and clean air. As they establish and start growing, these newly planted trees can be susceptible to browsing. The conventional tree guards or tubes used to protected individual trees have been plastic, due its durability meaning the guards can withstand being out in the elements for the period of time that the young tree needs the protection that they offer. As a protect, Sussex Flow Initiative have been committed to reducing the amount of plastic being used as part of our natural flood management woodlands, ensuring that the plastic guards are collected in when they have enabled the tree to grow to a stage that it can withstand any browsing. Reusing the guards as many times as possible and then ensuring they are recycled when they can no longer be used to protect trees. Ensuring we are not leaving them in the environment to choke the tree as it grows or break down into smaller pieces. Reducing use of plastic is our first priority: Not using a tree guard is the most sustainable option. As a project we have been seeking to establish riparian woodland and cross-slope woodlands through processes or using techniques that don’t require individual tree protection. Some of the methods we have been using are:

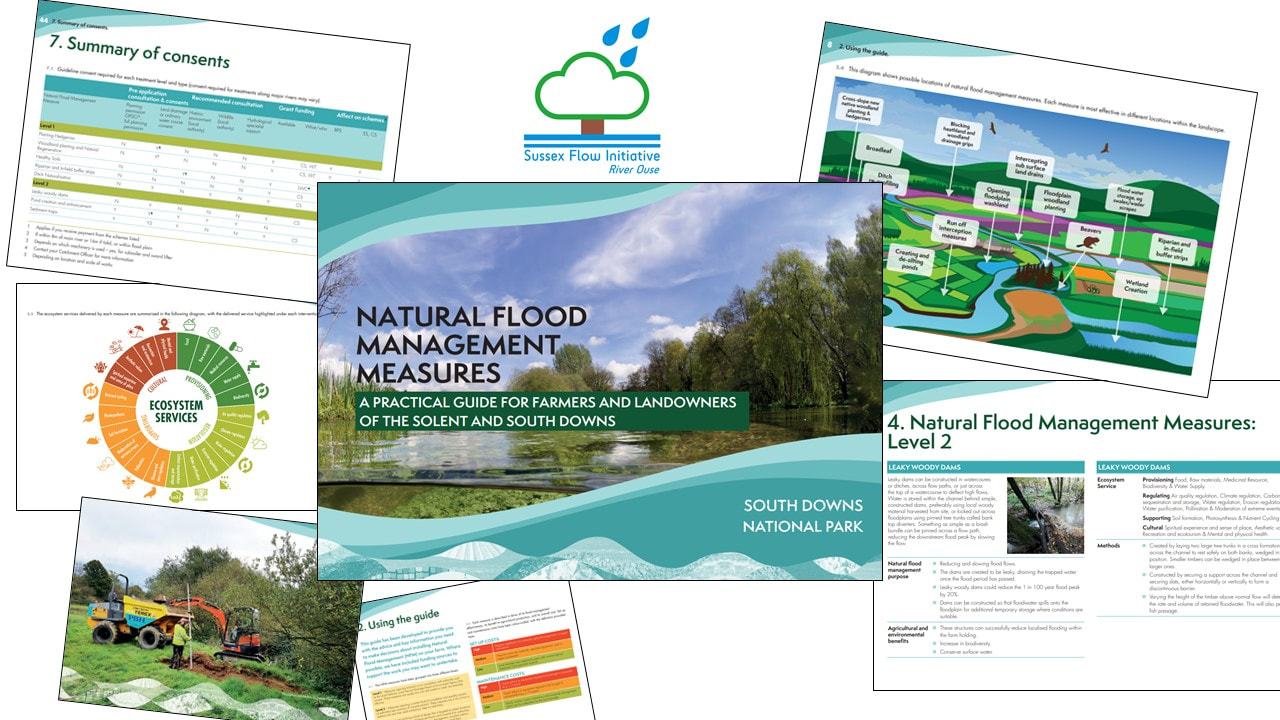

Re-using existing guards: We continue to monitor past plantings and have been actively revisiting sites to remove guards from planting carried out at the start of the project. We then reuse these guards, as well as we donating them to other projects, such as the charity the Childrens’ Forest, thereby mean new plastic guards aren’t used.  Removing guards from established hedgerow, guards collected in to be recycled Removing guards from established hedgerow, guards collected in to be recycled Recycling guards when they are no longer usable: The removed guards that we aren’t able to reuse due to damage or degradation are sent off to a local business that recycles them into recycled plastic products, such as decking boards and benches. Sussex Flow Initiative and the South Downs National Park Authority have created a Practical Guide for Farmers and Landowners for implementing Natural Flood Management measures. This new guide takes you through three levels of interventions from the quick and simple to the more complex multiple benefits schemes. Information is also included on costs and consents required for undertaking these works.

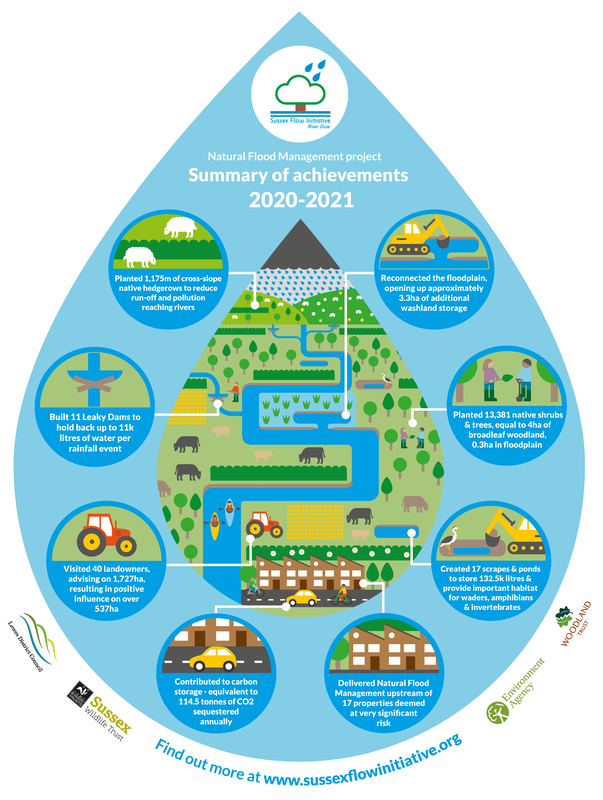

You can download the guide here The global pandemic has impacted everyone and it has had an effect on what and how we have delivered Natural Flood Management across the Ouse Catchment this year. We have however manage to continue the incredible work of previous years in creating a climate resilient landscape for both people and wildlife. A few highlights from 2020/21:

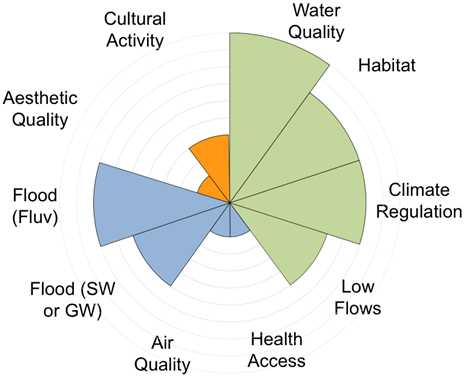

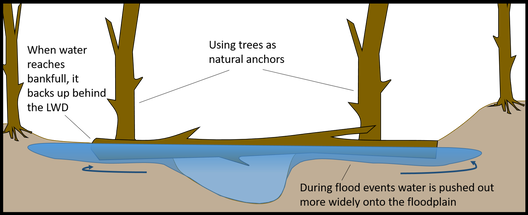

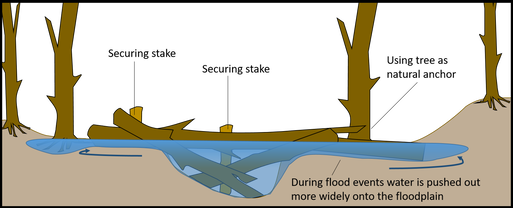

The above is just a selection of the work undertaken in 2020/21, the full annual report and the summary report go into great detail on what has been achieved and its impact. Thank you to all our landowners, volunteers and partner organisation for their support in a challenging year for all. Large Woody Debris (LWD), or leaky dams is one of the most utilised Natural Flood Management technique. In the right locations they can provide a cheap and easy way to reducing flood risk, particularly when applied at a catchment scale. The range of benefits these structures provide, is only matched by the diversity in their style and construction method. Ranging from naturalistic dams utilising materials from the site in which they sit, to heavily engineered structures made from fabricated materials. They all aim to reduce flood risk by intercepting the flow of water in watercourse and helping to restore river-floodplain connectivity, thereby reducing flood peaks, slowing water velocities and attenuating flow by storing water on the floodplain. At the Sussex Flow Initiative (SFI), we are interested in all of the benefits that leaky dams provide, but we are particularly excited about their potential for making our landscapes more resilient to the extreme and unpredictable events of climate change. The benefits wheels below (taken from the Environment Agency’s Working with Natural Processes evidence base) helps to illustrate just how many benefits leaky dams can have across a whole range of ecosystem services. SFI aims to create naturalistic structures that blend into the landscape, utilising local material where possible. There are a variety of types of the LWD, the three main types used by the project are outline below. Further information on these can be found in 'SFI's Leaky Dam Guidance Document'. Types of LWDBanktop diverters Large woody debris is positioned and fixed across the banktop in streams and ditches, engaging high flows, holding back water and encourage it out onto the floodplain. Leaky dams In addition to a banktop diverter, woody material is added into and secured within the channel. This therefore means the structures are active earlier, at lower flow rates. The leaky construction maintains the watercourses base flow and ensure there is still fish passage. Gully stuffing Woody materials is positioned and secured longitudinally within the channel to slow the flow of water and trap sediment. This type of LWD is typically used within relic drainage ditches within heathlands and woodlands. These naturalistic structures emulate the natural process of wind blown trees or the dams that would have been created by beavers before they were lost from our landscape 400 years ago. The images below show how these structures can could just be a collection of sticks to fall length trees secured in place, but they are all:

SFI is delighted to have been awarded a Silver award at the Countryside Protection for Rural England (CPRE) Sussex Countryside Awards 2020. The award recognises the partnership projects work with landowners and local people to reduce flood risk within the River Ouse catchment through working with and resolving natural processes. Congratulations to all the amazing projects and individuals who won awards - more details can be found by click here. Thank you to our project partners, landowners, local communities and volunteers for their support, passion and hard work in protecting and enhancing Sussex. The Sussex Flow Initiative has been running since 2012, working with and restoring natural processes to reduce flood risk. Each year we produce an annual report on what the project has delivered. These reports focus primarily on the amount of habitat created and restored, as well as the amount of water stored through the variety of natural flood management measures. Natural flood management measures undertaken by SFI not only help to reduce flood risk and increase drought resilience of our landscape, but they also provide a whole range of other ecosystem services. An example of the ecosystem services delivered by SFI is the regulating service of pollination, through the planting of our native flowering trees/shrubs to slow the flow and connect habitats. Ecosystem services are flows of benefits, which could be compared to the money payed into your bank account, creating a stock 'your bank balance'. Natural capital is the stocks generated by through the flows of these ecosystem services. Storage ponds created to intercept land drains within the upper catchment of the Ouse. What is social and natural capital? Social capital is the benefits delivered to human health and wellbeing, and natural capital is the additional benefits delivered to nature and wider society, such as carbon storage for climate regulation, pollination for food production, and water purification. Working with New Economics Foundation, we attempted to document the true societal value of the partnership project work delivered by the project. Social Capital Benefits of Sussex Flow Initiative Using bespoke surveys and spreadsheets, we found some really interesting insights into the true societal value of this project, here are some of the findings:

Volunteers creating leaky dams and hedgerow planting to slow the flow. © SFI Natural Capital Benefits of Sussex Flow Initiative The UK government’s Ecosystem Services Databook was used to help calculate the wider natural capital benefits that the project has brought to society. In the eight years of the project, it has generated an incredible £1 million of public and natural capital benefits. This equates to a whooping £125,000 of benefits for every year of the project since 2012.

These figures are based on seven key ecosystem services; timber provision, air pollution removal, carbon sequestration, flood regulation, water quality improvements, biodiversity and volunteering. Due to insufficient information/data it was not possible to calculate all the multiple societal benefits of all the work carried out by the project. Therefore, the true value will be greater than the £1 million. A significant portion of the work undertaken by the project delivers benefits that are incremental and will accrue greater value each year, for example the carbon storage will accrue over the lifetime of trees planted. Having this evidence is an incredibly powerful tool, and a fantastic step to demonstrate real and wider value of the nature-based solution work of SFI. What a year it has been!! The 5th wettest winter, the wettest February of records, and five named storms. As a result, the impact of our work was seen almost instantly. A few highlights from 2019/20:

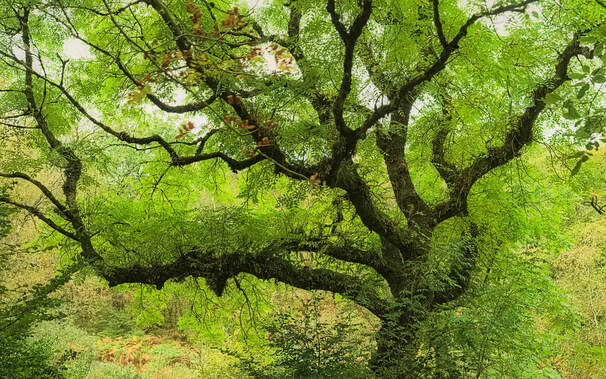

The above is just a selection of the work undertaken in 2019/20, the full annual report and the summary report go into great detail on what has been achieved and its impact. Thank you to all our landowners, volunteers and partner organisation, without them we wouldn't be able to have delivered what we have. Hedgerows do much more than just mark field boundaries. Some of the benefits they provide are easy to see – they provide shelter for livestock, food for wildlife, carbon storage, corridors for species to move between habitats, and are an important habitat in their own right. What is less obvious is the important role they play in the wider landscape, and in particular how they help to improve the quality and quantity of water in our rivers and streams. Image: Mature hedgerow © SFI By acting as a physical barrier to overland water flows during heavy rainstorms, and with their roots helping to increase water infiltration rates in the soil adjacent and under them, hedgerows help to slow and reduce the amount of water that reaches our rivers, contributing to flood risk reduction downstream. In the process of slowing overland flow, hedges also help to reduce the erosion of soils, and the delivery of sediment and contaminants to our rivers and streams. During World War II, food shortages lead the government to incentivise hedgerow removal to increase food production. This practice continued for several decades due to agricultural intensification; with the size of farm machinery increasing, hedgerows were grubbed out to create larger fields to accommodate these machines and maximise productivity. This intensification has also lead to more soil compaction from large machinery and high densities of livestock. The result is that hundreds of km of hedgerow, in Sussex alone, are now missing from the landscape and our fields are more susceptible to surface run-off and erosion. Thankfully, existing hedgerows now have more legal protection and many farmers see the benefits of planting new ones to help protect valuable soil and water resources, and to provide forage and shelter for livestock in an unpredictable climate with more extreme drought and storm events. In the Ouse catchment, with the help of funders and volunteers we’re supporting landowners to plant hedges in the right places. Image: Hedge planting © SFI In the short term, we can’t replicate the structural and biological diversity of the missing ancient hedgerows, but by utilising historic maps, where possible we can plant new hedgerows in the same locations, and perhaps an ancient seed bank will germinate when conditions become favourable. We can also identify fragmented habitat that would benefit from being connected by hedgerows, encouraging wildlife to move throughout the landscape. For the Sussex Flow Initiative, we support the planting of hedges, and we can provide maximum funding when they are located in key areas for Natural Flood Management – specifically when the hedgerow will be positioned across a hill slope or on a floodplain. Although we know that hedgerows interact with water and can help to slow overland flow, exactly how much, which tree/shrub species are most effective, and at what scale hedgerows need to be restored to begin to reduce flood risk downstream, is still uncertain. What research has shown, is that infiltration rates can be up to 60 times greater in fenced woodlands/shelterbelts1, compared to adjacent pasture, but we don’t know how transferable this is to hedgerows. Research is now underway at Bangor University, where PhD student Bid Webb is investigating how trees and hedgerows influence infiltration rates compared to adjacent pasture. They are also investigating whether tree age and species play a role. So far, the group’s results suggest that Fraxinus excelsior (Common Ash) has the greatest potential (of the seven species being studies; Alder, Ash, Beech, Birch, Chestnut, Oak and Sycamore) to increase soil infiltration, due to it having the highest fine root biomass, with over 50% of this biomass in the top 10 cm of soil, and the greatest proportion of large pore sizes in the soil. The large pores enable water to quickly infiltrate into the soil, reducing overland flows. The findings suggest that loss of Common Ash from the landscape due to the spread of Ash dieback (a fungus called Hymenoscyphus fraxineus), may have implications for our landscapes’ flood resilience. Image: Ash tree © Tim Haynes We’re eagerly awaiting the results from the group at Bangor University, and will use the findings to inform our NFM delivery. We will also be encouraging and supporting universities in the South East to carry out similar research in the lowlands, on the local soils, and focusing on the root morphology of species commonly found in our local hedgerows.

References 1. Carroll, Z.L., Bird, S.B., Emmett, B.A., Reynolds, B. and Sinclair, F.L. (2004). Can tree shelterbelts on agricultural land reduce flood risk? Soil Use and Management, 20, 357-359. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed