|

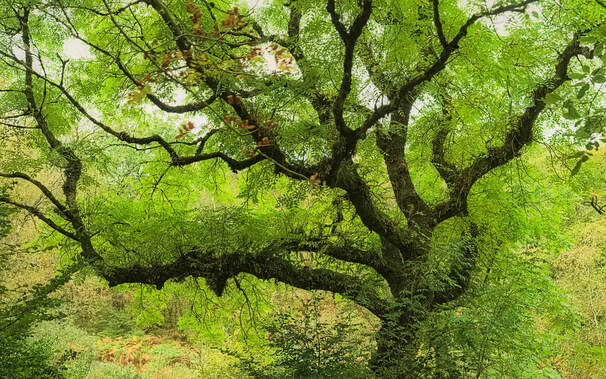

Hedgerows do much more than just mark field boundaries. Some of the benefits they provide are easy to see – they provide shelter for livestock, food for wildlife, carbon storage, corridors for species to move between habitats, and are an important habitat in their own right. What is less obvious is the important role they play in the wider landscape, and in particular how they help to improve the quality and quantity of water in our rivers and streams. Image: Mature hedgerow © SFI By acting as a physical barrier to overland water flows during heavy rainstorms, and with their roots helping to increase water infiltration rates in the soil adjacent and under them, hedgerows help to slow and reduce the amount of water that reaches our rivers, contributing to flood risk reduction downstream. In the process of slowing overland flow, hedges also help to reduce the erosion of soils, and the delivery of sediment and contaminants to our rivers and streams. During World War II, food shortages lead the government to incentivise hedgerow removal to increase food production. This practice continued for several decades due to agricultural intensification; with the size of farm machinery increasing, hedgerows were grubbed out to create larger fields to accommodate these machines and maximise productivity. This intensification has also lead to more soil compaction from large machinery and high densities of livestock. The result is that hundreds of km of hedgerow, in Sussex alone, are now missing from the landscape and our fields are more susceptible to surface run-off and erosion. Thankfully, existing hedgerows now have more legal protection and many farmers see the benefits of planting new ones to help protect valuable soil and water resources, and to provide forage and shelter for livestock in an unpredictable climate with more extreme drought and storm events. In the Ouse catchment, with the help of funders and volunteers we’re supporting landowners to plant hedges in the right places. Image: Hedge planting © SFI In the short term, we can’t replicate the structural and biological diversity of the missing ancient hedgerows, but by utilising historic maps, where possible we can plant new hedgerows in the same locations, and perhaps an ancient seed bank will germinate when conditions become favourable. We can also identify fragmented habitat that would benefit from being connected by hedgerows, encouraging wildlife to move throughout the landscape. For the Sussex Flow Initiative, we support the planting of hedges, and we can provide maximum funding when they are located in key areas for Natural Flood Management – specifically when the hedgerow will be positioned across a hill slope or on a floodplain. Although we know that hedgerows interact with water and can help to slow overland flow, exactly how much, which tree/shrub species are most effective, and at what scale hedgerows need to be restored to begin to reduce flood risk downstream, is still uncertain. What research has shown, is that infiltration rates can be up to 60 times greater in fenced woodlands/shelterbelts1, compared to adjacent pasture, but we don’t know how transferable this is to hedgerows. Research is now underway at Bangor University, where PhD student Bid Webb is investigating how trees and hedgerows influence infiltration rates compared to adjacent pasture. They are also investigating whether tree age and species play a role. So far, the group’s results suggest that Fraxinus excelsior (Common Ash) has the greatest potential (of the seven species being studies; Alder, Ash, Beech, Birch, Chestnut, Oak and Sycamore) to increase soil infiltration, due to it having the highest fine root biomass, with over 50% of this biomass in the top 10 cm of soil, and the greatest proportion of large pore sizes in the soil. The large pores enable water to quickly infiltrate into the soil, reducing overland flows. The findings suggest that loss of Common Ash from the landscape due to the spread of Ash dieback (a fungus called Hymenoscyphus fraxineus), may have implications for our landscapes’ flood resilience. Image: Ash tree © Tim Haynes We’re eagerly awaiting the results from the group at Bangor University, and will use the findings to inform our NFM delivery. We will also be encouraging and supporting universities in the South East to carry out similar research in the lowlands, on the local soils, and focusing on the root morphology of species commonly found in our local hedgerows.

References 1. Carroll, Z.L., Bird, S.B., Emmett, B.A., Reynolds, B. and Sinclair, F.L. (2004). Can tree shelterbelts on agricultural land reduce flood risk? Soil Use and Management, 20, 357-359.

0 Comments

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed