Droughts are natural events, and there are lots of streams or sections of stream that we would expect to naturally flow intermittently due to climate, weather patterns and fluctuations in underground stores of water. Such streams are inhabited by organisms with adaptations that allow them to subsist in these habitats. For example, many aquatic invertebrates lay eggs that are covered in a gelatinous membrane, preventing the embryos from drying out, ensuring that they can survive without water during dry spells. Other aquatic animals actively seek refuge during droughts, burrowing in wet muds or sheltering in damp areas. However, not all aquatic organisms are well-adapted to cope without water, which is one reason why droughts, particularly those brought on by, or exacerbated by human activities, and in streams for which drying up is uncharacteristic, can be problematic for wildlife (not to mention us). In recent weeks you may have seen images of the Environment Agency working hard to rescue fish left without enough water to survive. In the UK, our native fish have few adaptations to these conditions, other than the ability to move and seek pools for refuge. In other more arid countries, some fish have evolved adaptations that allow them to travel over land to find suitable habitat, or burrow into mud and produce a mucus cocoon. There are lots of human activities that increase the likelihood of rivers and streams drying up or experiencing low flows. One of the most significant is our conventional approaches to land and water management. Historically, land management has considered water somewhat of a nuisance, and every effort was made to encourage water off of the land and out to sea as quickly as possible. After removing trees and hedgerows, digging ditches, installing land drains under fields, constructing river embankments, and dredging, channelising and clearing debris from our rivers, water now travels quickly downstream. In most cases, Natural Flood Management is focused on reversing these activities and restoring the ability of the land to slow and store water. In doing so, water is once again allowed to infiltrate into soils and slowly drain into surface waters, or percolate deeper into soils and replenish groundwater stores, resulting in a more steady supply of water to rivers and streams. By reintroducing woody debris to streams, not only does it help to ‘slow the flow’ but it also encourages a more diverse flow pattern (which is often lacking due to channelisation and lack of debris) and influences geomorphological processes, including the formation of scour pools. These pools can be an important refuge for aquatic organisms during droughts, and if the stream does completely dry up, woody debris is likely to benefit burrowing invertebrates by providing heavily shaded areas where sediment remains moist for a longer period of time. These benefits for wildlife were visible when we visited some of our woody debris dams earlier this week. It was easy to see the changes in streambed level, and the scour pools that have been formed since we installed the features. The stream was not flowing and had largely dried up, but there were numerous scour pools downstream of woody debris that were visibly sheltering a (crowded) community of aquatic invertebrates. It was great to see that our NFM work is bringing benefits year-round. The multiple benefits provided by NFM, are why we at the Sussex Flow Initiative are so passionate about this approach to reducing flood risk, by restoring and working with natural processes.

0 Comments

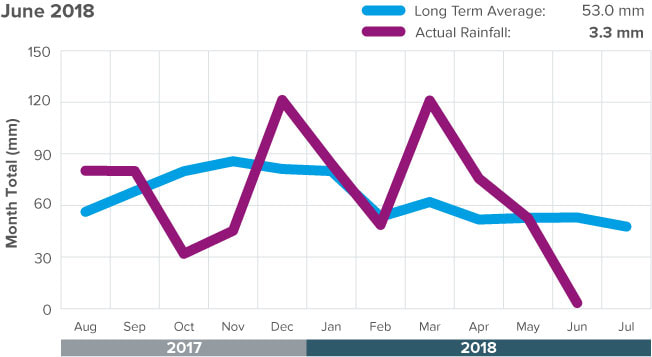

Rina Quinlan, Project Officer, Powdermill Catchment Rina Quinlan, Project Officer, Powdermill Catchment In April 2018 I started my role as a Natural Flood Management project officer for the Sussex Flow Initiative (SFI) in the Powdermill Stream Catchment in East Sussex. SFI has had some fantastic results with ‘slowing the flow’ of the River Ouse catchment since 2014 and as a result, the partnership has been extended to this new river catchment. My job is to help alleviate the rising amount of localised flooding, by using natural measures such as hedgerow planting. In this role I advise on natural flood management (NFM) and work with natural processes (WWNP) to help landowners and communities make their land and homes more water resilient in times of heavy rainfall. More importantly at the moment, it also helps us to be more resilient to drought. The Powdermill stream runs between historic Battle to the north and Crowhurst village to the South. It sits within the High Weald Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (HW AONB) and its undulating hills, wild flower meadows, ancient and ghyll woodlands are familiar characteristics of this landscape. Water, however, flows rapidly down these steep valleys, causing streams to overflow and high surface water run-off from hard urban surfaces such as roads and houses. Engineering solutions have tried and failed to improve the flooding situation for this catchment and historic drainage practices and canalising of rivers, as well as increasing intensity of land use for urban development and agriculture have exacerbated the scale and severity of flooding. However, recognition for the multiple benefits NFM and WWNP can provide to local communities and wildlife is gaining more and more traction throughout the UK amongst many stakeholders. My role is relatively simple. By creating woody debris dams, tree and hedgerow planting, pond and washland creation, this helps reduce flood peaks and slow the flow of water before it reaches homes at risk. Crucially WWNP also makes our landscapes more resilient to drought by storing more water for longer on the land. If that wasn’t enough, NFM also greatly improves wildlife habitat for a multitude of species, provides shade and water for grazing animals, mimics natural processes, stores and cleans water, and much more. As a passionate conservationist and advocate for ecosystem restoration, I take great delight in explaining to others that much of my role entails mimicking the things that a beaver - one of our natural ecosystem engineers – would do!! It’s a great job, and I’m looking forward to seeing what we can achieve. Rina Quinlan can be contacted at [email protected] or 07595 452038 |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed